A motorcycle ran into me and broke my leg rather badly, so I'm coming home soon. This post was written a little over a week after the accident, from a hospital bed in Rabat, Morocco.

Introduction

I'm just going to go through what happened in a rather anodyne manner here, and not speculate about what comes next. There'll be plenty of time for conclusions later on. Recently, I've been kept busy with much simpler things, like figuring out how to put pants on, or which way to position my leg so that it hurts less.

In summary, a motorcycle ran into me when I was on my bicycle, as I was on my way home for dinner on Monday, July 17. This broke my left femur, and also did damage to my femoral nerve. This means I can't raise my left foot, and I've lost all feeling along the top of that foot. I can expect to regain some usage of that nerve in about six months. When neural healing is complete in 18 months, I may be at about 70% effectiveness along that nerve.

I've had three operations: A first emergency procedure a 2 AM to asses the damage and do some cleaning, a second one in Ouagadougou to throughly clean the wound, and a final, more intensive operation in Rabat, Morocco. All three operations went well. I'm ready to travel now, and I should be leaving Rabat late tomorrow night, and arriving in L.A. on Thursday.

This is my first real chance to write any of this down. Typing with an IV needle in my hand didn't seem like a good idea. The IV needle came out last night.

Thank God I speak French. With the exception of the surgeon in Morocco and PC staff, basically everybody I've spoken to in the past week-plus has not spoken English. It was also a great comfort being able to read my medical report in Ouagadougou right after it was written, rather than waiting a day or two for a translation.

The Accident

Here's what I remember: I was biking home along the paved road from the training center to my host family, and I started to make my normal left turn. As far as I know, I did what I always did, that is, signaled my left turn, and checked for oncoming traffic. Suddenly, I felt a blunt force on my left side, and the next thing I knew I was looking up at the sky, with one of the little 125cc Burkinabè motorcycles under my left leg. I don't think I lost consciousness; I think this was just the normal blank one gets around a trauma. I instinctively tried to move my left leg, and it didn't move at all.

A crowd formed pretty quickly, and I remember someone looking like he was going to move the motorcycle out from under me. Putting on my best command voice, I said “ON NE TOUCHE SURTOUT PAS À LA MOTO !” (Above all, one does not touch the motorcycle – a little awkward in English, but a powerful command in French). It worked: People backed off. The first volunteers came on the scene quickly: Madison and Atticus. They helped back the crowd off, too. I remember at one point, some guy was getting close, and even brushed against the motorcycle; my French command voice came back with “You! In the Green Shirt! Step back!” And he did.

With one week's remove, I can't recall a vivid image of how afraid I was,

or how much

pain I was in, but I do remember that I was very scared and in substantial

pain. I remember it in a removed fashion, almost as if it happened to

someone else. I do remember that Madison was really there for me then.

Madison, I'll always be

greatful to you for that. She held my hand, told me what was going on

around me, and made me know that I wasn't alone. That was my whole world

at the time.

Around then, the Peace Corps car arrived. There was some talk of loading me into the car to take me to the local health clinic, but I emphatically vetoed any idea of moving me before a doctor or other medically competent individual said it was safe to do so. And I'm glad I did! Given the nature of the injury, I think it's quite likley that more nerve damage would have been done if I had been moved without first immobilizing the leg. I also insisted that they cut my pants away, rather than removing them – “on coupe, on ne retire pas!“ Score another one for me.

My host father, Yacouba came forward at some point. The look in his eyes! Somehow, seeing him like that was a great comfort too.

After some amount of time – maybe 20 minutes? – someone came up waving a leg brace, so I'd know it was OK to let them get to work. They did, and I was somehow transported to the clinic in Léo (probably on a stretcher in the Peace Corps SUV). At this point, Atticus came with me. I think he has some EMT training, and having a strong guy around is always a good thing.

The Clinic in Léo

Léo has a pretty good health clinic. I think it's sponsored by a German organization, or maybe the German government. Anyway, at the clinic there they cleaned up the wound some, and started giving me painkillers. Sweet, sweet painkillers. I also remember Atticus asking me if I wanted to see the wound, and I said “no,” and then immediately looked down and saw bone visible on my left leg. Eeeeewww!

Atticus took some picutres in the clinic:

My host father actually works in the clinic. As I was being bundled up for the trip to Ouagadougou, he and his son, Skander came by. I had bought candy for his younger brother's birthday. Giving it to the family anyway seemed like the thing to do, even though it was a little weird. Skander is about to enter 9th grade (3ème). I remember he looked really distraught, so I said to him “I'm going to be OK. It will be fine.” Somehow, doing that made me feel better, too.

The Trip to Ouagadougou

They loaded the stretcher into a Peace Corps vehicle, and drove up to Ouagadougou. Atticus came along with me, and I remember that he was a huge comfort.

Thankfully, I don't remember too many details about that trip. It was, in some ways, the worst part of the whole experience, The trip was long – I think maybe 3½ hours? There were a number of checkpoints along the way. I remember hearing 8? Most were unofficial. I don't completely know what the deal is, and I've never seen one (except staring at the roof of the vehicle while there were bright lights outside), but apparently at night, big speed bumps get built, and traffic is stopped by local groups for some reason or other. I remember Atticus saying “Holy crap, what is that?” at one point, but I didn't ask what was going on. The pain was coming back, and the road was not smooth. The ersatz checkpoints were particularly bumpy, and I was very much afraid of further damage being done to my leg.

Atticus was great the whole way. He played some music, we taked some, and he let me be quiet when that worked better.

When we got to Ouaga, I learned that the clinic was another 30 minutes away, depending on traffic. At this point, the painkillers were wearing off. Ouagadougou's road are paved, but very bumpy. That last 30 minutes was excruciating. I was maybe a little delirious by the time we got there, and fairly screaming for more painkillers.

According to my medical report from the hospital, I was admitted at about 11 PM. I had a “good state of consciousness” upon admission, but I wonder if that wasn't after the new painkillers started taking effect. Or maybe it was just me calming down because I was in a safe place. They cleaned up the wound with iodine

Operatons in Ouaga

The hospital in Ouaga was initally a little scary. The power went out a couple of times as I was being ferried about, and nobody even broke their stride when this happened. Indeed, during my stay the power went out a couple of times every day, but only for ten or twenty seconds. I guess the important stuff has an uninterruptible supply, and things like my ceiling fan rely on backup generators or something that take a few seconds to get going.

I was in the hospital in Ouaga for four nights. After doing an emergency cleanup that night, they put me on painkillers and installed me in my room. This was basically my view:

The room has one of those electric beds where you can raise and lower the back part, and an air conditioning control, which I promptly adjusted from 20 degrees up to 26. Remember, for the past month I'd been sleeping in a room that was probably about 40!

The next day, a little after lunch time (some else's, since I had to fast for the operation – but food was the last thing I wanted anyway), they did the second operation. This was under a local anesthetic, administered to my spine. The only pain I felt was from the IV needle being put in my arm, and from the two needles in my spine (the first a local anasthetic so that the second isn't as painful).

I was fully conscious during the operation, but to my surprise, it wasn't so bad. I couldn't see what they were doing (thankfully), but they were speaking French, so I knew what was happening. They were instructed to do a minimal operation to stabalize me for travel, clean out the wound, attend to any acute damage that was visible, and stitch things up. The cleaning actually felt good, and it was comforting knowing that road grime and whatever was being removed. While they were operating, they saw the nerve damage, so I first heard about it then and there. The medical report noted the damage the previous night, but I was too out of it at the time.

The surgeon said that my femoral nerve was intact, but “effiloché.” I had to look that up. It's a really evocative word, that means “reduced to strings, like when you rip up rags.” Decomposing the word, it's sort of “en-string-ed.” “Shredded” sounds bad too, but effiloché sounds both romantic and utterly disgusting. So I've got that going for me.

Polyclinique Notre Dame de la Paix

It turns out that's the name of my hospital. I've never experienced a kinder, more lovely group of people in my life. People were constantly stopping by my room to wish me “meilleur santé” (better health). The doctors explained absolutely everything, and stayed to chat. They guy whose job it was to clean me up after I used the bedpan (after three days, mind you) stopped by in the afternoon to wish me well. The security guard came by numerous times, and recommended that I listen to some Afrobeat music on the TV to give me energy.

My cellphone still worked, and I had just bought data, so I had plenty of internet access. I could even reliably make VOIP calls, any time of day!

I did have a couple of episodes of pain in my time there, and there was always the stress of knowing that I had to go to Morocco (or possibly the US?) for the repairative surgery, but other than that my experience at the Polyclinique was lovely. The food was pretty good, too. I wish I had pictures of all the wonderful people there. Sadly, that just didn't occur to me, with all the other things that were going on.

One negative spot was with the guy from Royal Air Maroc whos job it was to issue me a “certificate of non-contagion” for air travel. This he did, but he also told the Peace Corps doctor that no way could I fit in business class with a knee that can't bend, because it's a small plane without the kind of business class seats that lie back. Only Air France flies out of Ouaga with a proper business class, and that's to Paris. After about an hour of back-and-forth, the Peace Corps doctor asked if it would work if they bought two business class seats, one behind the other, and removed the seat in front. Yes, in theory, this would work, said the Air Maroc guy, with some reluctance in his voice. He warned that the flight crew might not do it.

This was a good example of a “Thank God I speak French” moment – forewarned is forearmed.

The Road to Morocco

First Try

Late in the night on Wednesday, the 19th, we made our first try at getting me on the 2 AM-ish flight to Casablanca. I think it's fair to say that I wouldn't be exaggerating if I were to call it a total fucking disaster.

I was feeling pretty good when we left. They put me on a portable emergency stretcher, and put that in the back on a Peace Corps car. It didn't quite fit in the back, so I had to kind of bend my head around an obstacle to make it work. But it's only 30 minutes or so to the airport, so OK.

When we get to the airport, I reported feeling fourmissemens on my foot. That's another delightfully evocative word: The feeling of thousands of ants (fourmis) crawling around. The English word “tingling” is decidedly prosaic, by way of comparison.

Well, turns out that nobody told the cabin crew about removing a seat from business class. Surprise, surprise. That tingling in my foot was starting to turn into pain, and we weren't budging. I think we sat in that parking lot for an hour, and it became pretty clear that the seat wasn't going to be removed, at least not that night. By this time, the pain in my foot was getting bad. I basically said that it was clear it wasn't going to work that night, and with the pain where it was, we should go back to the hospital. They gave me 800 mg of Ibuprofin, but it did nothing.

By the time we bounced through traffic for 30 minutes and made it to the hospital, the pain was excruciating. They were getting the painkillers ready, and they opened the back door. I then shifted my foot and… the pain lessened considerably. Acting on a hunch, I asked them to lift my foot a bit. The pain disappeared. I was totally surprised, but also delighted – no need for pain meds!

Here's what happened, I think: Remember, with the nerve damage, I can't pull my foot up. On a good stretcher or a bed, that's OK, because there's some soft cushioning under the heel. On an emergency stretcher, all that weight gets concentrated on one point, and because I was crammed in the back of a car I didn't quite fit in, I couln't move around. For over an hour.

Second Try

The next day, I (relatively politely) raised holy hell. I had very little faith that Royal Air Maroc would actually remove a seat for me. But, balanced against this was the fact that as long as the reconstructive work wasn't done, there was a risk of doing further damage. It was impossible to book Air France the next day anyway, because that flight leaves around noon, so that left us with Royal Air Maroc.

They did, sort of, give me the option of going through Paris straight to the US My thought was that if I were to go through Paris, turning back and going to Morocco takes about as long as going to, say, DC. Medically, it's obvious that getting treatment in Paris would be best, but I accept that they're not set up to do that; but going straight on to the US seemed medically sound and maybe possible. They did, in the end, give me a choice, but it came with a lot of caveats, like “we might not be able to schedule a surgeon in the US soon” and “there might not be seat availability” and “in the US, it's really your responsibility to schedule medical visits.”

So, basically I had no real choice but try for Morocco again.

This time, the Peace Corps did everything they could to make the transport work. They used the hospital's ambulance and a real, cushoned stretcher. They hopped me up on painkillers right before leaving, and gave me more to take in the plane, in case there was a problem. They also arranged so I didn't have to go through the airport – the ambulance drove up to the plane.

For some reason, they put me in economy, but as long as they could remove the chair in front of me, or tilt the back totally forward, that would be OK. The plane was late coming in, so I sat in the ambulance for a good long while, but on a proper stretcher that was fine.

Finally, my stretcher got carried up the stairs to the back of the plane, where I got to watch the maintenance guy try to push the seat back all the way forward. No dice. Then he tried to take the seat out. Then he went back for a tool to try to take the seat out. Then he went back for another tool, did some swearing, and tried to take the seat out. At this point the other passengers had boarded, and were looking on in puzzlement.

At the very last second, the eight guys carred my stretcher back down the stairs, over to the front entrance, and back up. Business class had a 1-2 seat configuration (one row on the left, two on the right), and was totally empty. They put me in the middle-front seat with my leg sticking into the passage by the restroom, threw some backpacks under it for support, and made ready. When I noted that the backpack pile would probably collapse, the steward grabbed one of those metal boxes they store food in, threw some pillows on top of it, and put it under my leg.

That actually worked pretty well. Here are a couple of pictures:

Not ideal, but I really wanted to get that operation done.

Casablanca Airport

When we landed in Casablanca, I of course had assistance. Only, they didn't have a wheelchair with a platform to support my leg. To get out of the plane, they put two wheelchairs facing eachother, with my leg on one. Fair enough, if you're very careful, for a short distance. They took me down the elevator car that they use to load food and stuff into the plane.

When we got to the terminal, the guy who helped me out of the plane jumped out of the truck and bolted. Then, the two guys whose job it was to get me through the terminal showed up, and more or less asked me how I expected them to get me through the terminal with my leg like that. Why didn't I use crutches? (Uh… because my leg is incredibly fragile and subject to further neurological damage, which is NOT the time to learn crutches.) They more or less stared at me for a good five minutes, but I stubbornly refused to disappear, or sprout wings.

Then they laughed, and stuck two wheelchairs facing eachother. They also told me about Système D, which there's apparenlty a lot of in Morocco. I had always understood the D to stand for se debrouiller (to un-entangle oneself), or se démerder (to un-shittify yourself), but in Morocco they seem to go with the more polite dépanner (to fix). In any case, going through a terminal with two wheelchairs facing eachother is a great example of Système D, making do with what's on hand. Especially when the guy in front doesn't pay attention, and the two chairs start going in different directions.

Peace Corps Transport to Rabat

After all that, imagine my joy when I was invited to sit sideways on a bench seat in a van for the 2-plus hour trip from Casablanca to the clinic in Rabat. My old friend, Système D. I couldn't sit straight up (my leg hurt if I tried, so I stopped trying quick), and there wasn't room to lie down, so I had to uncomfortably half-incline with no back support. One of the PC medical staff picked that moment to tell me that technically, it was illegal that I wasn't wearing my seatbelt.

FFS. Yes, if you get a $50 ticket for a seat belt violation, you will have my abject apologies for my having so wontonly had my leg immobilized in such a way as to make it impossible to wear a seatbelt as I painfully spend two hours in the van you brought that doesn't work for my condition.

Clinique Rabat Zahar

I arrived at the Clinique Rabat Zahar I guess around 10 AM on Friday, the 21st. That afternoon, I went into surgery.

Surgery

They wheeled me into an operating theater, where some Arabic music was playing. This was another “thank God I speak French” moment – it's so very nice being able to commmunicate with your doctors and nurses. They plugged me into some painkillers and such, and stuck the two needles in my spine. I asked if I wasn't getting a general anasthetic. They changed the IV bottle, and I felt a lovely cool sensaition in my left arm. I felt liquid spilling down it my arm and tell them, then I realize it's the drug, so I said “never mind, it was just a sensation.” I asked if that was a general anasthetic. The anesthesiologist said that they will give me something to calm me down, so I was OK with that. They put a tube under my nose, and I asked if I should breathe through my nose our mouth (hey, with that many drugs in me, I had a right to be a little dumb). They said it was oxygen and good for me. I didn't believe them, and I took deep breaths through my nose.

BOOM

I wake up, and I'm being wheeled out of the theater. Somehow I'm babbling to a nurse that I speak a bit of Arabic. Oh? La illaha ill allah. “You're half muslim already!” I went the rest of the way with la illaha ill allah, wa Muhammed al-rasul allah (modulo misspellings, “There is no god before God, and Mohammed is his messenger”). I knew I was being a little silly. Also, I was coming down from general anasthetic.

COLD

So cold. I was in a hot room, and felt a cold like I had never felt before. My entire body was shivering. Somewhere I've heard about lowering body temperature for a surgery, so I figured this was normal and OK. But oh my God. Cold. So very cold.

Into my room. Still cold. Blanket. Would I like another blanket? Oh, yes, yes I would. Still cold. Shivering. Cold. A little warmer? Still cold, but some heat returning? Cold, but getting warmer. It's OK now. I won't be cold forever. I can sleep.

After the surgery

After the surgery, it's been pretty straightforward. There was a ilttle pain, but I came off the painkillers pretty quickly. It took some adjustment to get the cast right, but now that it is, it's fantastic. Crutches aren't all that hard, especially when you no longer have an IV needle in your hand.

Dr. Bouhouch, the Surgeon

Dr. Bouhouch has been fantastic. He also speaks English at about the level at which I speak French, so when I was being debriefed on my condition, we switched back and forth. He's talked me through absolutely everything, and listened carefully when we had a little problem with my cast. My left foot has a problem with tight shoes, and at first the cast was triggering that; he fixed it brilliantly. With a saw. In my room. On Sunday. Looking at my final X-ray, the Peace Corps doctor was frankly admiring the work he did. He's gone above and beyond; I really do feel like he's a partner in my recovery. Based on everything I've seen and experienced, I am absolutely delighted with Dr. Bouhouch and his staff.

Dr. Victor

Dr. Victor is the Peace Corps doctor. He's been wonderful, too: Dedicated, competent, and professional. He's also a character… Born in Moldova, he was a doctor in the Soviet army, working alongside his Cuban comrades in Angola back in the day. The Moldovan language is basically Romanian, so I was able to trade some Romanian swear words with him. I'm glad I got to know Dr. Victor.

Hospital Staff

The hospital staff here in Rabat has been delightful. I'd say 60-80% of them speak French well, and half speak it substantially better than I do. For most of the time, I haven't been my usual self, but I still managed to chat and enjoy the company of people whose job it is to schlep me meals, empty my pee bottle, and pretend not to notice the stench coming off me. The hospital here is a little more manual than my image of a US hospital – for example, to raise or lower the bed, I have to hit the call button, wait for someone to come, and then tell them how far to turn the crank under the bed. They're always cheerful, and nice, and helpful. I really appreciated that when, for example, they were helping me to stand up on crutches for the first time, and take my first faltering steps to the elevator and back.

Shower!

As I was writing this, I finally got to take a shower! After 8 days, I was noticing the smell. When the accident happened, I was already a little overdue for washing my hair with shampoo. Being violently thrown to the ground, transported hither and yon and undergoing three operations didn't do my hair any favors, either, not to mention the rest of me. I've been shaving with my electric razor for a couple of days now, but that was it. I basically couldn't imagine trying to clean myself while the IV needle was in my hand, and it was only removed last night. The final step was to get basically a leg condom to keep the water off the plaster and bandage.

Oh, yeah, I just found out that I'm leaving the hospital tomorrow night (Wednesday), for a flight out of Casablanca early in the morning on Thursday. I'll connect in Frankfurt, and take (I assume) Lufthansa to LAX. The good news: I'll get some frequent flyer miles out of the deal.

Food, Facilities and Some Pictures

The food has been great. The facilities are fine, if a bit basic. I do miss the electric bed I had in Ouaga – it's nice to adjust your bed timy amounts at frequent intervals, but socially impossible when someone needs to come crank it for you. The TV gets six channels: Five in Arabic, and one in German (!). I get six FM radio stations, or sometimes one – there's a radio tower right outside my window, so I think that's maybe interfering with my reception.

I have 3 GB of pictures of the operation in Rabat, including a video. Wanna see? I don't. I'm keeping them in case they're of use to a future doctor.

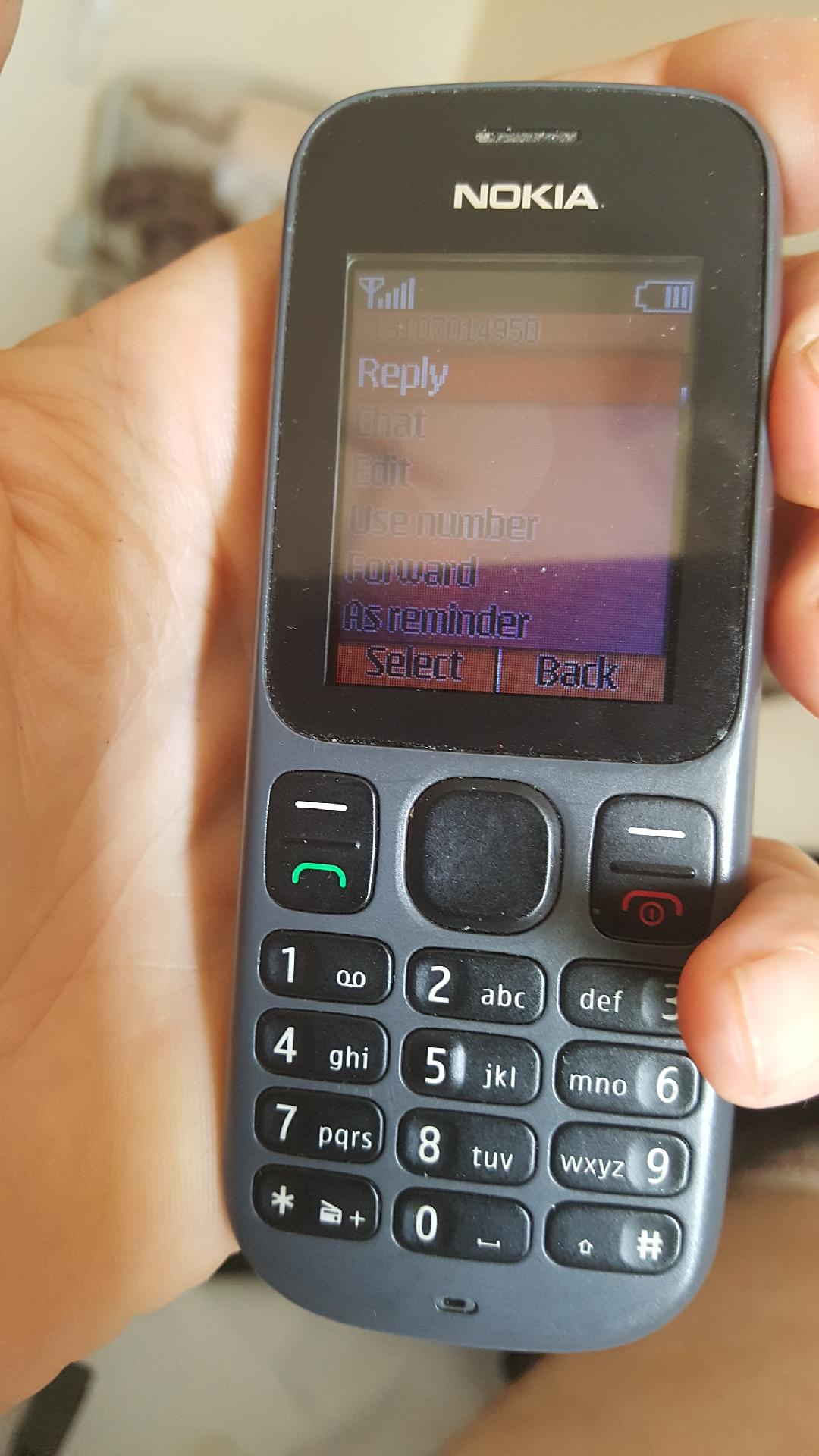

No Internet, no Phone!

Here's the wonderful phone the Peace Corps issued me upon arrival:

This has been a major source of frustration. I'm supposed to be organizing care for myself in the US, but they land me here, give me this phone, and tell me I'm not allowed to call anyone other than in-country Peace Corps staff with it. No internet at the clinic, of course.

Now, for a typical PC post, I can see the logic of the PC supplying a phone for official use, and typically, official use doesn't include calling home, or using the internet. Besides, the PC office and the hotel where they put up volunteers have Wifi. But, for a hospitalized volunteer, using the internet to contact home and research medical care options is exactly official use. This is precisely what I was instructed to do, and it was made impossible by a blanket policy that makes no sense in my situation. Hospitalized volunteers are the ones in the most accute need of contacting home, and they are, in essence, prevented from doing so.

If I could have bought a SIM card for my phone, I would have, but it turns out you need to go in person with a photo ID to buy one.

The Peace Corps did a lot of things right, and I'm grateful for the medical care I've received. I know that when I go back to the US, I'm heading straight into the bureaucratic buzzsaw that is the US healthcare system; that's not the Peace Corps' fault.

With all big, bureaucratic organizations, some things fall through the cracks, and some policies are senseless. I accept that. In this case, we found a workaround: One of the PC staff here brought his phone to me in the hospital, so I could call the PC staff member in DC who's handling my case. Only she'll be out for three days starting tomorrow and she kind of wasn't ready for my directness and preparedness, so instead her supervisor and I worked through all the needed preparations over the course of an hour. Some of it involved undoing faulty assumptions that had sprung up, due to the lack of communication. This has been exacerbated by a problem with Verizon that prevented my sister from calling me.

So, rather than spend $5 on a data plan so I could make the needed preparations, we forced a Morocco staff member to stand around for an hour while I made a much more expensive call on his phone to straighten out everything that had gone wrong. There's a reasonably chance that the doctor I end up going with won't be the one I'll be seeing next week, since that's one of the choices that was made based on bad assumptions, without a chance for me to give new input when I learned new, relevant information. It was frustrating for everybody, and so unnecessary.

Conclusion

It's fair to say that I had two major frustrations with the Peace Corps' handling of my case: Transportation to and from airports, and the Catch-22 where I'm required to coordinate with home, but prevented from doing so.

With that said, I am so very greatful that I was with the Peace Corps when this happened. One of my big reasons for joining the Peace Corps was the (relative) safety and the availability of quality medical care. I absolutely and without reservation stand behind that decision. You do not want to be on your own in the event of an accident in the thirld world. I'm very greatful for the excellent medical care I've received.

I"m also very greatful for how friendly, helpful, and genuinely caring everyone was, both in the hospitals and in the Peace Corps in both places. Sure, there were a couple of frustrations, but this ain't easy. I am impressed with how everything went, all things considered.

No grand thoughts on the Peace Corps or my future yet. On the blog I figure I'm good for one more medical update, and then maybe a final post with some longer-range thoughts in a few weeks or months to wrap things up.